Many Internet sources give a rather vague definition of native advertising and link it to product placement and sponsorship programs on radio and television. IAB.Russia (probably the mane instutute that know something about NA for sure) notes in its research reports that there is confusion among customers about the formats among themselves due to the relative novelty of the format and the lack of clear boundaries of this concept. Though before we drew a line between native advertising and other similar types of advertising in the previous posts, let us outline its general properties thought the perspective of legal acts.

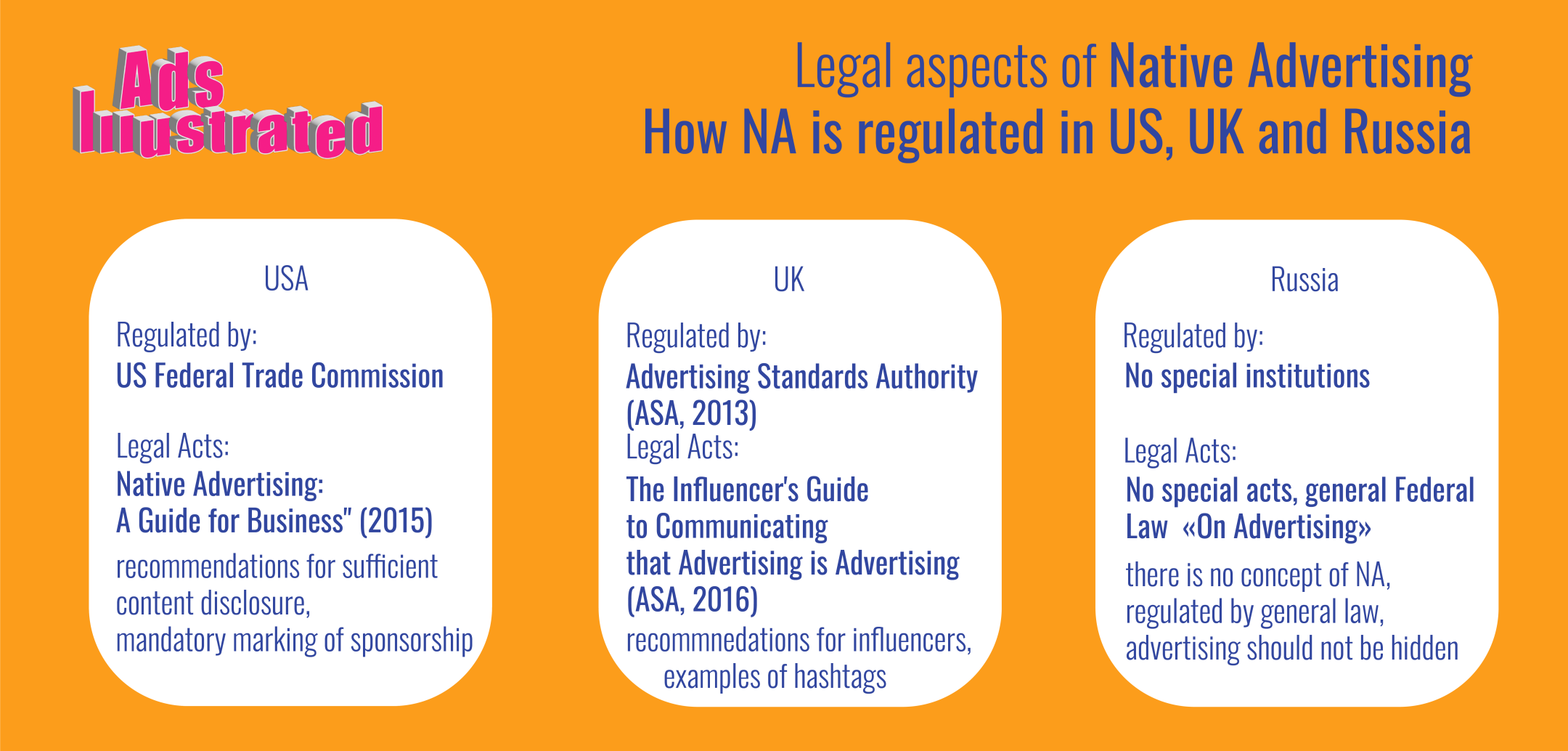

The understanding of native advertising is still rather vague also because it is actually regulated differently by the laws of different countries. The question of what is considered native advertising and what is not depends largely on the country in which you publish the advertisement and its legislation. For example, while the US and UK have a history of developing regulations regarding native advertising for over 10 years, in Russia there is still no legislation in this area.

So, what does the law say about native advertising in different countries? Let’s look at the example of the USA, the UK and Russia.

Native Advertising in USA

It should be noted that the understanding of native advertising varies depending on the country and its legislation. For example, the US Federal Trade Commission, a pioneer in legislating the concept of native advertising, regulates native advertising with its guide “Native Advertising: A Guide for Business” (2015), which defines sufficient disclosure of the advertising nature of material as a mandatory condition of native advertising, in other words, material cannot be published without the label “sponsored content”.

Native Advertising in UK

In the UK, the self-regulatory organization Advertising Standards Authority (ASA, 2013) regulates native advertising. The ASA code requires that all marketing materials must be recognizable as advertising. In 2019, the ASA released a new guide for Influencers, The Influencer’s Guide to Communicating that Advertising is Advertising (ASA, 2016). The ASA recommends using hashtags #ad, “Paid-for-ad” and “Advertisement” to indicate that content is paid advertising, while “Sponsorship”, #sponorship, “Recommended by” and other ASA signatures are less acceptable because they do not indicate that the blogger has been paid for the publication.

Native Advertising in Russia

In Russian law, for example, the concept of “native advertising” does not exist at all. However, there are separate articles that may be applicable to it. The law “On Advertising” specifies that “this Federal Law does not extend to… references to a product, the means of its individualization, the manufacturer or the seller of the goods, which are smoothly integrated into works of science, literature or art, and which are not advertising information in themselves”. In other words, native advertising is not considered hidden and does not violate the law if it is an integral part of the story, a cultural product. However, in the event that regulators do not consider a native article to be a product of art, it would be considered improper advertising without the advertising mark. Antimonopoly authorities in some cases identify the concepts of product placement, which often refers to native advertising in Russian practice, and latent advertising. It should be kept in mind that hidden advertising is expressly prohibited by the law, which defines it as advertising that “influences the consciousness of consumers without their awareness, including through the use of special video (double sound recording) and other means”. Thus, native advertising, including a significant part of its rapidly growing part – Influencer Marketing, is not directly regulated by Russian law, which makes the publisher primarily take care of itself and avoid possible conflicts with control authorities by marking the native article as sponsored.

Russian practice is still in its infancy, but the first cases clearly show that the Federal Antimonopoly Service is paying close attention to Influencers and the native advertising they produce. An example of recent years is the precedents with the native advertising of Russian bloggers on the video service Youtube, where videos featuring alcohol products and online casinos (this types of products are prohibited or restricted for advertising in Russia) were recognized by the FAS (Federal Antitrust Service) as advertising banned in Russia. But in another case, the FAS did not check the online casino advertising on YouTube, explaining to the plaintiff that it had nothing to do with Runet (part of the Internet sites with main content in Russian).

Such close attention of regulatory authorities to the activities of bloggers and new forms of advertising integrations on the Internet signals the presence of problems in transparency in relations with its consumers. And, although according to recent studies, users have learned to see advertising in bloggers’ “sincere” posts, the question of the line between a blogger’s personal opinion and advertising remains open.

Interested in Native advertising? Check what you missed in my previous posts about Native Advertising:

A quick guide to Native Advertising – part A. Native adverising from W to F?

A quick guide to Native Advertising – part B: Native Content rules the world of Advertising

A quick guide to Native Advertising – part C: Product Placement as a Native Content

A quick guide to Native Advertising – part D: Sponsored Content

A quick guide to Native Advertising – part E: Special Projects

Wow, thank you. So I need to find out how it is regulated in my country.

thank you, Olga. Good to know!

Ok, I will go to check the law right now

I remember the case with Ivleyeva!