Switzerland normally isn’t exactly cutting edge when it comes to cultural trends. However this isn’t only for the bad. It seems that Switzerland so far has withstood the trend of severe austerity measures in the arts & culture secture that countries like Denmark (-2% per year!), the Netherlands and the U.K. have seen over the recent years. The Plateforme 10 in Lausanne, described as a whole new art district seems to become another landmark museum adding to the already lively cultural landscape of Switzerland. Even before its opening in 2019, Platforme 10 has sprung to life in various online and offline activities. Not surprisingly it recently hosted a symposium on digitzation in the museum: „Rising to the challenge. Digital innovation in museums.“

In the recent years there was some resistance of many museums to certain aspects of the digital like for example social media, which might relate to a conservative mindset deeply ingrained in a profession that is concerned with preservation and conservation. The curator Zhang Ga points at a deeper problem, a general hostility towards technology, rooted in the idea that technology is a foreign alienating power while art seems to reflect some kind of authentic human nature. (> Simendon On the mode of existence of technological objects). However both, culture and technology are created by humans and thus are an „embodiment of human knowledge“.

Oonagh Murphy from Goldsmiths College in London challenges the idea of museums as places of resistance against change by quoting from Karsten Schubert who notes that museums have always been changing:

it could be said that one of the greatest myths about the museum is that it is an oasis of calm untouched by the storms of policts and history. Nothing could be further from the truth. Overt time, the museum has responded to political and social shifts with seismic precision. It’s very success is the result of its exceptional flexibility and capacity to adapt.

And meanwhile It seems that even in middle Europe the discussion fortunately has moved on from the question of „Why do we need this?“ and „how do we do this“ to the third step „how do we get this right“? The main outtake of this event for me is that we maybe should not be concerned with the digital at all anymore. We’ve hopefully arrived in a postdigtal age, referring to the fact that nowadays the digital triggers our awareness more often through its absence than through its presence. Everything has become digital or digitally enhanced. The digital has arrived at the core of our society and our lives.

Interesting from a museum perspective, as Martijn Pronk Head of Digital Communication at the van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam points out, is the fact that this does not change the core of a museum. At the core are the purpose, the museum’s mission, its objects, it’s visitors, it’s staff. The objects don’t change. The sculpture, a painting, a vase will be the same. What is changing is the way objects are presented, communicated and mediated and how museums engage with their audiences. However, Nadine Witlisbach director of the Fotomuseum Winterthur explains that photos in themselves are a complex form of abstraction (> Vilem Flusser). The contemporary photo per se is digital and hence the museum needs to experiment with new forms of presentation in order to reflect contemporary photographic practices. And digitzation definitely affects the experience of space and objects. Spaces become digitally augmented through information mapped to it, like for example Google Maps, Trip Advisor, etc… and the Internet of things predicts the same for more and more objects. Additionally many audience members nowadays experience the space by interacting with their own digital devices.

Catering for audiences either digital or analogue has grown more complicated nowadays due to the fact that those audiences have become more and more diverse. Nadine Witlisbach points out that the Fotomuseum Winterthur caters for three main audiences: local visitors, national visitors and online visitors. The recent changes in the strategic aims towards becoming a competence center for photography obviously had affects on the communication. The new website for example, catering for an international audience caused some issues with the local visitors. So it is important to have „a critical conversation about the conflicts of interests“ museums might be facing.

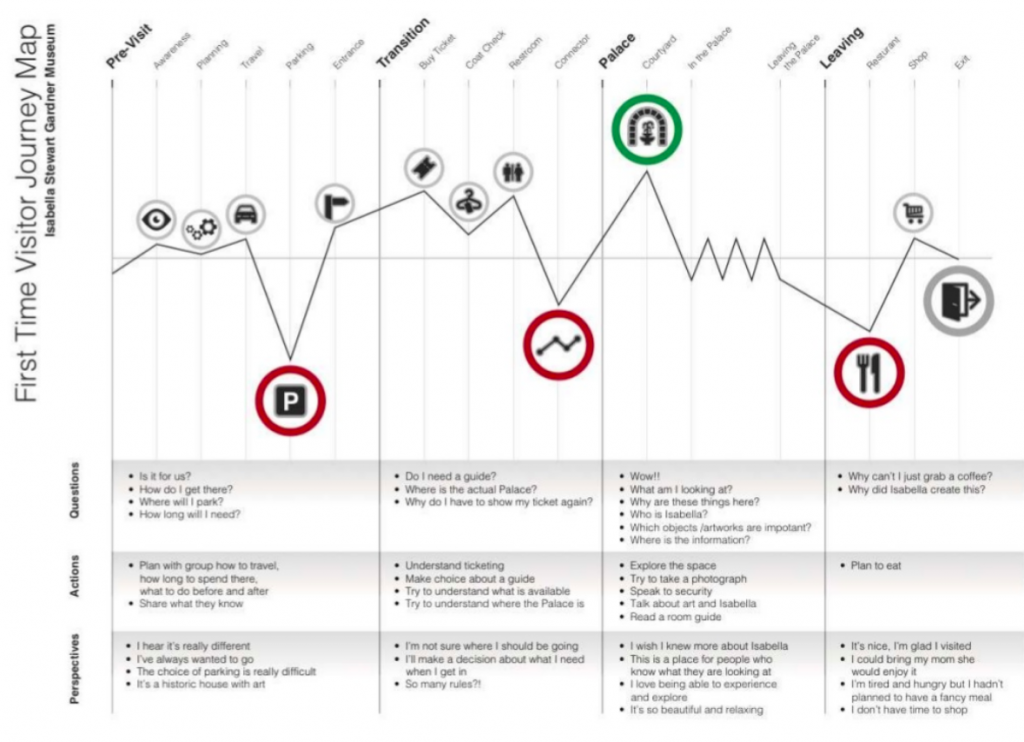

Either way, as Murphy states in her talk, museums „should not become a showroom for the latest technology“. Every activity of a museum should be a result of strategic planning. How this can be done beautifully was shown by Carolyn Royston chief experince officer at the Cooper Hewitt in her earlier work for the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The museum, founded in the early 20th century by the eccentric philanthropist and art collector Gardner comes with a „difficult visitor experience“. „Gardner wanted to produce an immersive experience“ that resulted in „no labels, low lighting, no linear narrative“. In her will she determined that the museum should stay forever as it was. On top of that, in 1990 thirteen art works with a current worth of about 500 Million Dollars were stolen and never retrieved. The museum decided for the empty frames to remain in their places. While the museum has since been modernised with the help of an additional new building the question remained how to improve the user experience in the original location. For me as a teacher in a design department it was great to see how Roysten and her team used service design as a method to achieve this.

Service Design is a human centered approach on developing services and therefore starts with empirical methods of collecting mostly qualitative data about how current users experience the museum. Theses findings were mapped out in a timeline: for example most of the visits started out in frustration because of the lack of parking spaces. Another interesting finding was that many visitors actually came because of the missing paintings and the story of the theft. The museum took these inputs, figured out, what they wanted to address and set up a list of projects, prioritized by what time and effort it would take to put them into effect. Again, following the Service Design method they started with simple prototypes and tests rather than with complex and complete solutions. One of the results is a 20 min audio-tour for every first time visitor that explains the museum from a first person perspective. It tells the story of the museum from the perspective of its founder. All in all the Gardner museum is a great example for what can happen when we stop talking about the digital and concentrate on the means to cater for the needs of an audience.

Further interesting references taken from the conference:

Scan the world: „Scan the World is an ambitious initiative whose mission is to archive objects of cultural significance using 3D scanning technologies, producing an extensive platform of content suitable for 3D printing.“

SMK open: „Making the (Swedish) National Gallery’s art collection freely available to everyone — for any purpose, ranging from fun to serious production. The objective is to make art relevant to more people.“

Arttalk: „arttalk ist eine interaktive Museums-App für Smartphones. arttalk verwandelt Smartphones in multimediale Ausstellungsbegleiter. arttalk bringt Museen in die sozialen Netzwerke.“

Ethix: „ethix schafft Räume und entwickelt Instrumente, mit denen ethische Risiken, die Innovation mit sich bringt, zum Nutzen von Unternehmen und Gesellschaft erhoben und produktiv bearbeitet werden können. ethix arbeitet interaktiv und stellt den Austausch mit PartnerInnen ins Zentrum.“